Click here for Hot Rod Magazine! |

What the average owner of a '54 Buick doesn't realize is that beneath all that crazy bodywork there is a completely new and superior chassis and steering

Possibly, because the older Buick Straight eights lacked good performance in the stock condition has been the reason that they have been all but ignored in the past by hot rodders. "Too much iron!" they shouted. This was true. An unbelievably heavy and inflexible monster, the straight eights were hardly any

In the various fields of competition hot rodding, Buick successes were few and very far between and were brought about by a small but determined group, well versed in the many necessary modifications required to make a Buick get off teh dime.

Most of these straight eight doings are now in the past, what with more advanced engines available, plentiful and relatively cheap. But then, even the new Buick V8's have been almost totally forsaken be lovers of speed and performance. "What can you do with that thing?" they

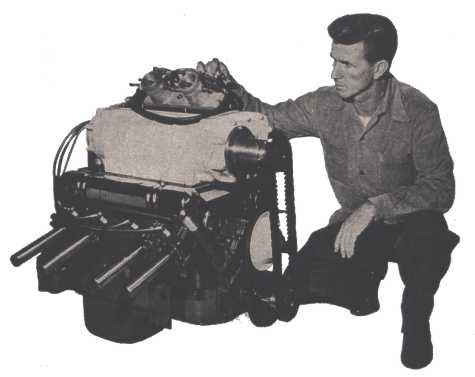

Walt Murray of South Gate, Calif. and his part-time partner, Roger Howie, of Bell, Calif., and each with years of pervious Buick competition experience, have arrived at their own solution to the problem. By using a completely stock '54 Buick "Roadmaster" V8 block and bottom end, these boys calculate that they

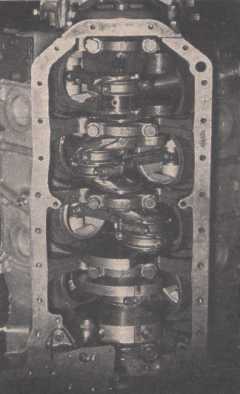

This four inch bore, 3.2 inch stroke, 322 cubic inch engine uses stock pistons, connecting rods, piston pins, rings and crankshaft. All that was done to the block assembly was to increase the piston-to-cylinder wall clearance by .001 of an inch and re balance the crankshaft, rod and piston assemblies. The heads were modified only to the extent of slightly enlarging the intake port area nad polishing the surfaces. The exhaust passages were also cleaned out, but these present a problem in that it is quite difficult to cover the entire length of the port without special, long shank tools or extensions. The combustion chambers are fully machined at the factory, assuring a consistent shape, volume and consequent compression ratio between all cylinders.

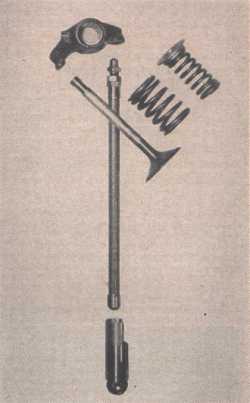

The valve gear is actuated by a Chet Herbert roller tappet cam with 280 degrees of duration and a lift of .515 of and inch at the valves. Adjustable tubular push rods, made from 5/16 of and inch outside diameter steel tubing are used, which necessitated enlarging the push rod clearance holes in the heads from 3/8 of an inch

The compression ratio is an even 8 to 1, obtained by using the thick (.050 of an inch) head gasket that is standard equipment in cares with convectional transmissions. Dynaflow equipped cars use a head gasket that is .015 of an inch thick, which increases the compression ratio to 8.5 to 1.

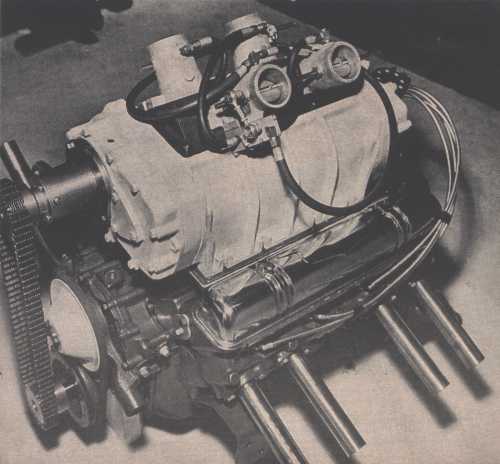

Perhaps the most interesting part of this particular engine is the blower. This unit was originally designed for use on 6-71 series 426 cubic inch GMC diesel two-stroke engines. The supercharge pressure, or boost, is between six and seven psi on the GMC engine and maximum blower

The manifold beneath the blower resembles a shallow cake pan, with openings cut into the sides that coincide with the intake ports in the heads. This

Carburetion problems are handled by a Hilborn fuel injection system. This injector represents the only usable remains from Chet Herbert's ill-fated four-cylinder two-stroke engine that demolished itself during a dyno run last year. The two pairs fo injector throats are mounted to a 45 degree adapter, which in turn is mounted on top of the blower.

Original plans called for the injector pump to be belt driven at the front of the engine, but this was scrapped in preference to a combination fuel pump, tachometer and ignition driving unit with a vertical shaft and a pair of bevel gears used to drive a cross shaft. This gearbox is now

Positive lubrication is assured the main, connecting rod and camshaft bearing by the stock Buick oil pump. Low pressure oil is metered to the "thrust" sides of the cylinder walls and valve gear in the heads, which drains back to the pan through the front timing cover, lubricating the timing chain and sprockets in the process. Additional low pressure oil is routed to the supercharger drive gears and any excess oil passes through a drain line connected to the ignition, fuel pump, tachometer drive unit.

Unfortunately, there is no information concerning the power output of this engine, the dynamometer runs being scheduled some time after this magazine goes to press. However, when the power figures are available, they will be published in the "Shop Talk" column of a future issue. And they should be pretty impressive.

All of the special parts of this engine were designed and built during off-hours by the owner, Walt Murray, an architectural and mechanical designer. The present design project, along with several others, is a set of magnesium rocker arms for the Buick that would not only increase the engine speed but would also eliminate the tedious chore of adjusting the hard-to-reach push rods to obtain the proper valve clearances. Roger helped out when he could be spared from the duties of his own shop in Bell, Calif.,

But don't go away! The Buick V8 engine holds many virtues that are unbeknownst to most hot rodders. For big bore, short stroke lovers, the Buick the the most. The four inch bore, used in all models except the 1954 "Special" (which is 3 5/8 inches), is the biggest in the industry. The 3.2 inch stroke is the shortest of any V8 with the exception of Ford and Mercury (3.1 inches), giving the Buick a stroke/bore ration of .8 to 1. With this design, engine torque is not only increased over a comparable long stroke engine, but is spread out over a wider rpm range, adding to the engine's flexibility. The torque produced by the 322 cubic inch 1954 engines varies between 295 pounds/feet at 2000 rpm to 309 pounds/feet at 2400 rpm, depending upon compression ratio and type of carburation. The advertised brake horsepower also varies, falling between 177 and 200 at 4100 rpm.In the Buick V8's produced for the "Super" and "Roadmaster" series in 1953, severe detonation was encountered after an engine had been in use for several thousand miles. This was caused in part by the relatively high compression ratios of 8.0 and 8.5 to 1, for standard and "Dynaflow" transmission types, respectively. The shapes of the combustion chambers and pistons were, however, perhaps the major contributors to the detonation problem. The combustion chamber was wide open, no provisions having been made for surfaces on the piston or combustion chamber itself to act as "quench" and "squish" areas as the piston neared top center.

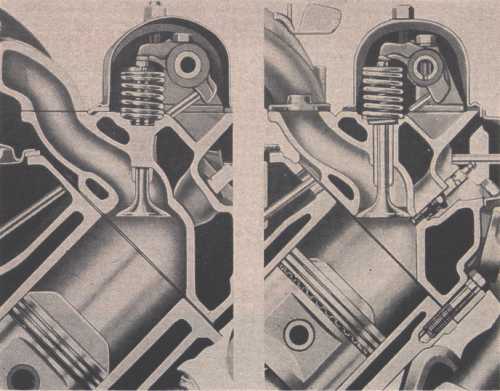

This condition prompted Buick engineers to redesign the combustion chamber and piston for the 1954 engines. As can be seen in the accompanying cut-away drawings, the width of the '54 chamber was narrowed by about 25%, leaving two flat spots at the outer edges. The pistons were made with corresponding flats. At top center, these flat areas come within .035 to .070 of an inch of each other, depending on the type of head gasket used. Thus, they form two "squish" areas that squirt the fuel/air mixture into the main combustion chamber cavity, maintaining a high degree of turbulence at a time when the engine needs it most. These same flat surfaces form two very effective "quench" areas that quickly cool the trapped mixture before it has a chance to overheat and detonate. With this arrangement, the combustion chamber cavity is even more compact than before, still offering all the advantages of the "pent roof" design, plus increased turbulence and cooling areas. Incidentally, the 1954 Buick cylinder head assemblies on all but the "Special" series are completely interchangeable with the '53 heads, provided that '54 pistons are also used. However, the '54 pistons are 1.85 ounces (52.447 grams)

The size and shape of the Buick V8 combustion chamber, in conjunction with the valves being placed vertically and in a straight line in the cylinder heads, offers something of a restriction in the size of the valves that can be used. This has been the cause of the objections voiced by hot rodders, who sometimes examine an engine and see only the obvious improvements that can be made. But there's more than one way to skin a cat.

Take the Buick camshaft, for example. It is ground from a steel forging, which is unique in the fact that it is the only overhead valve V8 that makes use of anything but cast iron for ta cam. It is certain that Buicks are not bothered by the wearing of cam lobes, a trouble that has plagued every other manufacturer of overhead valve V8 engines. A squint at the valve timing figures shows that the Buick cams for '53 and '54 are by far the wildest stock cam in use in a V8. In fact, from the standpoint of valve timing alone only the most radical "super race" cams can compare with it. The intake opens at 25 degrees after bottom canter, lift at the valve is .378 of an inch. The exhaust opens at 70 degrees before bottom center, closes 42 degrees after top center, lift at the valve is .350 of an inch. This results in a cam with 282 degrees of intake valve duration, 292 degrees of exhaust valve duration and an overlap of 67 degrees. The stock Buick valve gear is good for at least 550 rpm before the hydraulic lifters "pump up." With light weight solid lifters, otherwise stock Buick valve trains have been buzzed in excess of 7000 rpm,

In any event, the Buick valve timing specifications show why the small exhaust valve works so well. The valve start to lift early, closes late and is lifted to a height equal to 28% of its head diameter, practically unheard of in this day and age.

Furthermore, theory and past experience inform us that the velocity of gases through the intake system should be close to 200 feet per second for best power, with a safe maximum limit of 250 feet per second before any restrictive effects are noticed. We are also told that the velocity of exhaust gases may safely exceed the velocity of intake gases by 60%, or between 320 and 400 feet per second before the power starts to fall off. Consequently,

The foregoing merely points out that the valves and ports in the Buick engine appear to be a handicap at first glance, but in reality there is no handicap at all, the whole problem having been worked out by some intelligent engineering in a slightly different direction, but giving the same results as larger valves with a lower lift and milder valve timing.

The Buick also scores in the matter of engine weight, always of interest to hot rodders. Previously, the lightest engine for the amount of piston displacement was the Cadillac, which weighed in at about 650 pounds, without the transmission. The Buick, with close to the same displacement, weighs about 625 pounds without the transmission. Actually, the Buick weighs about the same as the '54 For V8 and Mercury engines, which certainly is a factor to consider when compared to an 860 pound Chrysler or a 780 pound Lincoln V8.

We have tried to point out the most attractive features of this engine without overlooking its shortcomings. In my own opinion, the '54 Buick V8 is definitely worthy of serious consideration for competition purposes or as a slightly modified passenger car engine. While the present supply of special equipment is restricted to camshafts, one or two dual four-throat intake manifolds and exhaust headers, there really isn't much more that's necessary to build a good piece of performance equipment. So there it is, hot rodders, take it from here.