Buick and Olds were the first, this year, to come through with all new aluminum engines of advanced design. While the 215 cubic inch displacement an d3.50 by 2.80 bore and stroke are common to both versions, there are some sharp differences in appearance, cylinder head and manifold design that make each engine stand out.

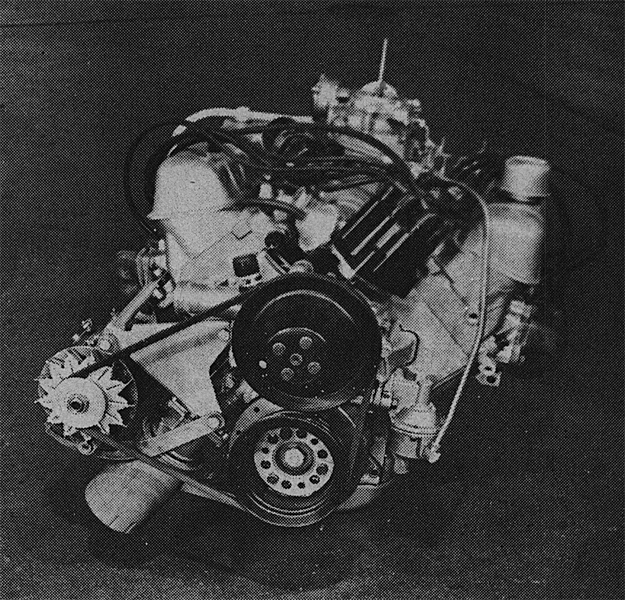

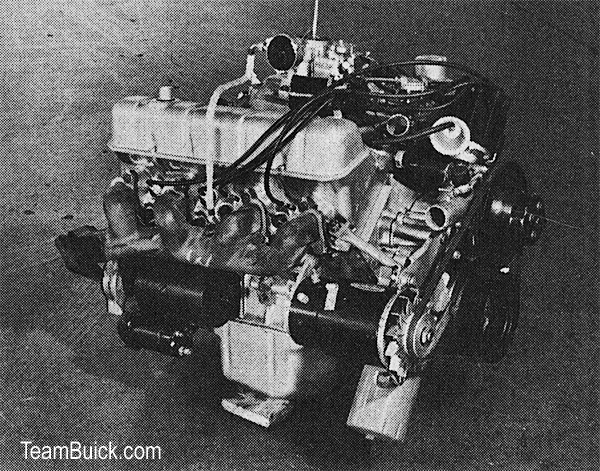

The most striking advantages, from a user's point of view, are the remarkably low weight of these power plants, just 318 pounds, for an output of 150 horsepower at 4,400 rpm on the Olds and 155 horsepower on the Buick. This power obtained from a stock engine, fitted with a single two-barrel carburetor, so that the possibilities are largely untapped.

The Present two-pounds per-horsepower ratio will no doubt move down to a pound-and-a-half per-horsepower, or even less, as normal development takes place.

Design with aluminum is different than with cast iron, and offers several manufacturing possibilities. Sand casting, with sand cores and patterns is one and follows the same methods as are now used in pouring cast iron blocks. A number of castings can be made from a single permanent mold, with the added advantage of superior finish and closer tolerances. Die casting makes use of pressure-injected molten aluminum poured into special dies. While its initial steps are comparatively costly, the long die life helps balance out costs.

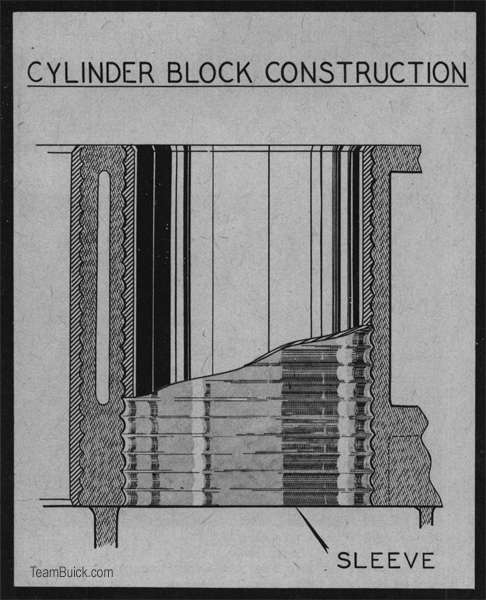

Die casting, being an automatic process, requires a direct withdrawal of the dies as the casting is completed. This has, so far, made it impractical to cast a block with a full cylinder deck. Instead, the cylinders are left standing free, tied in only at the bottom of the block. This poses sealing problems what will no doubt be solved shortly, but as yet this is not the most desirable solution, A wet sleeve design, where the cylinder liners are removable, makes die casting very practical, but this method is too expensive for passenger car use, by Detroit mass-production standards.

Buick and oldsmobile hoped for a semi-permanent mold casting, with cast-in iron sleeves.

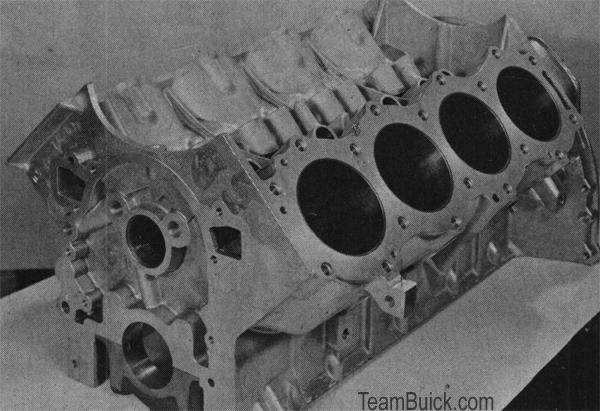

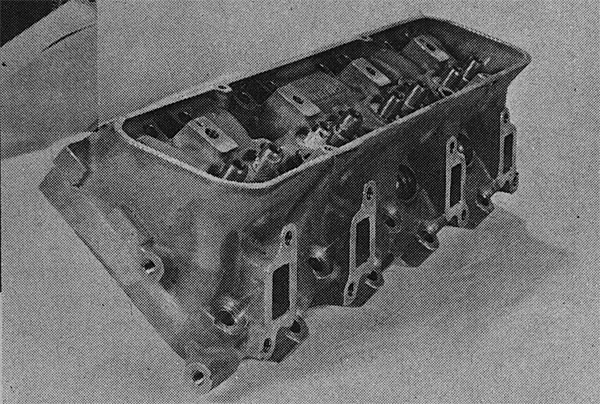

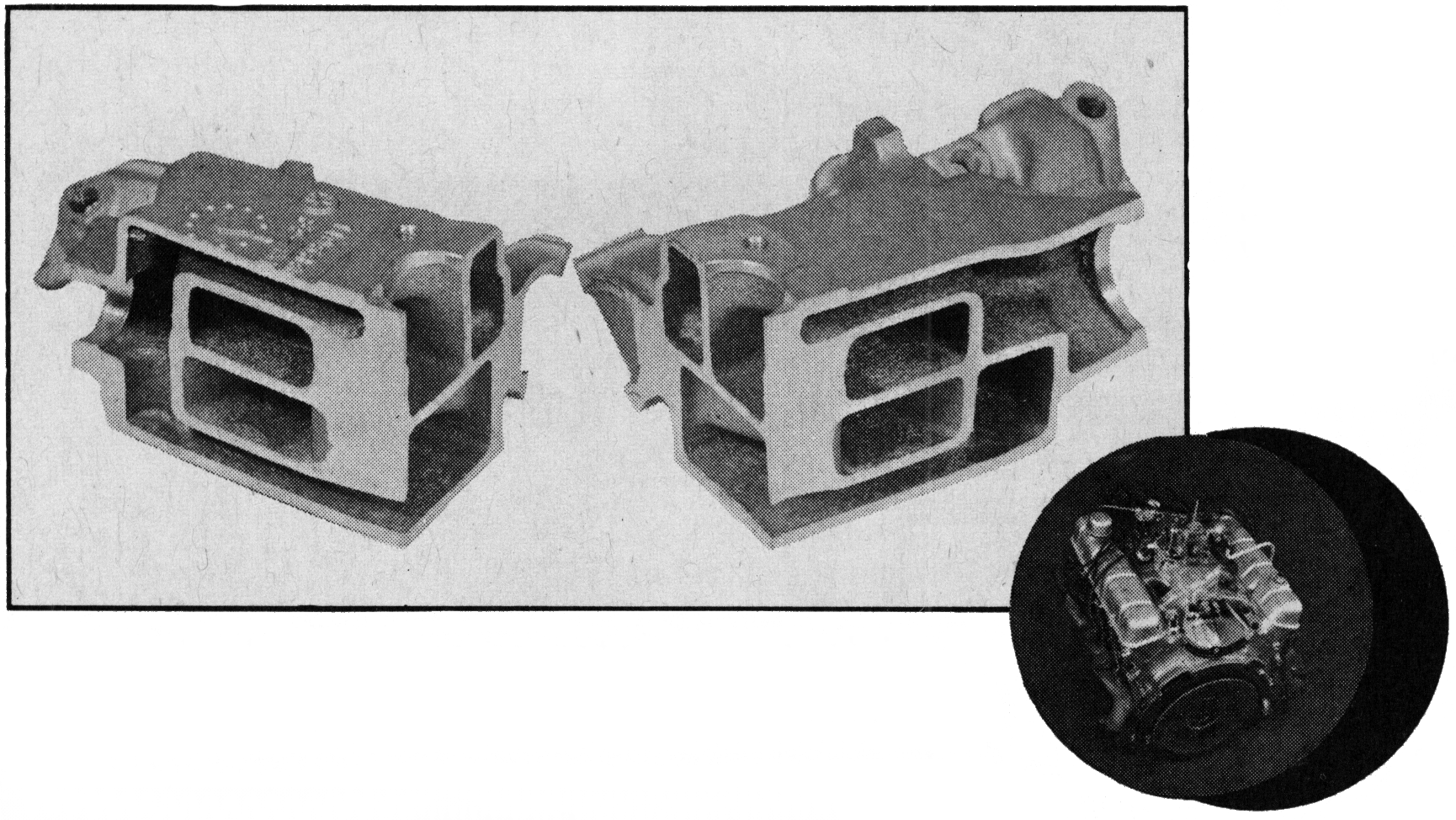

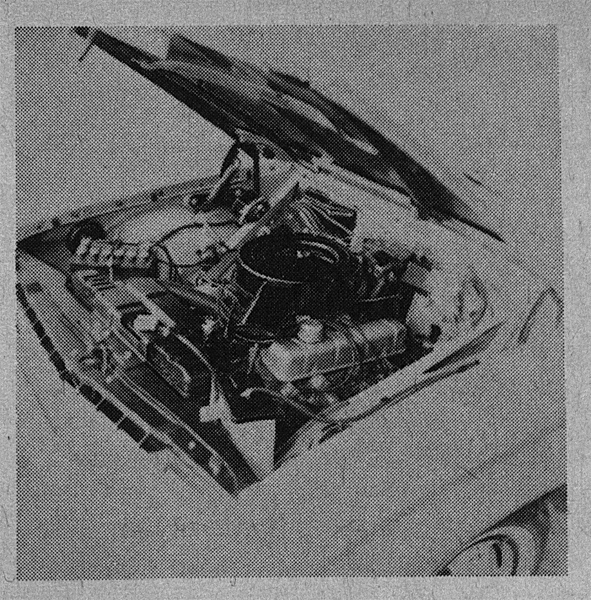

Olds engine compartment can be spotted by round filter base cast into manifold and by inclined rocker covers. Its aluminum block is a semi-permanent molding with cast-in iron sleeves. Reinforcing webbing shows good quality.

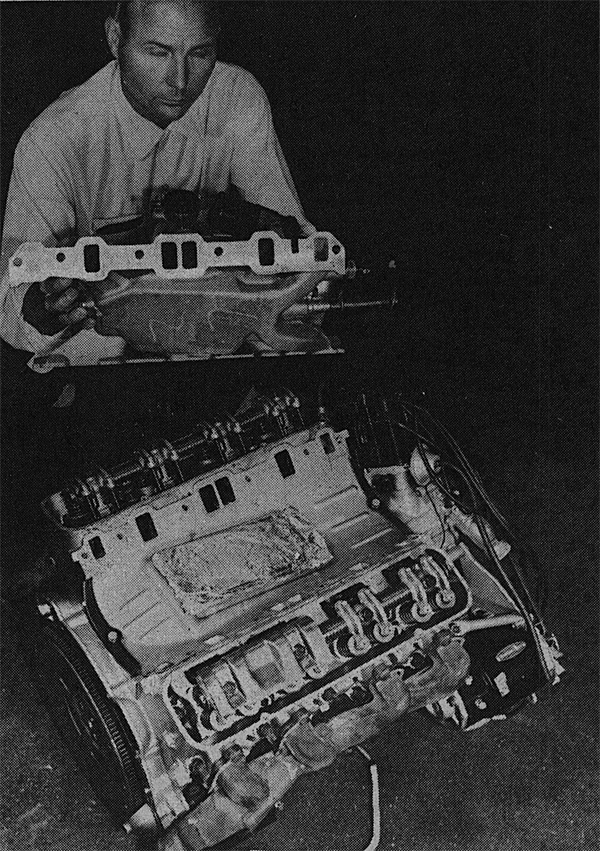

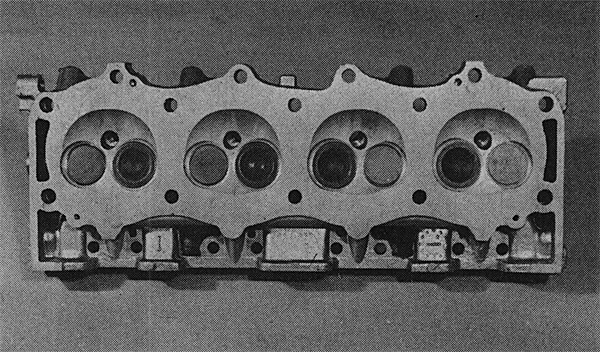

Small Rochester two-barrel (left) is housed in air filter and silencer container. Cylinder head,too, is aluminum (below), has cast Iron guides and steel seats. It also is cast by the semi-permanent method.

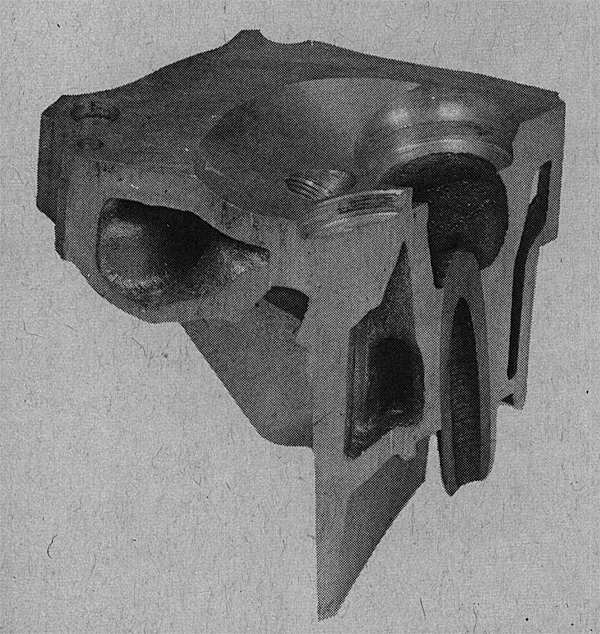

The .093-inch thick cast iron sleeves have flat, wide threads turned on their outsides to provide good grip.

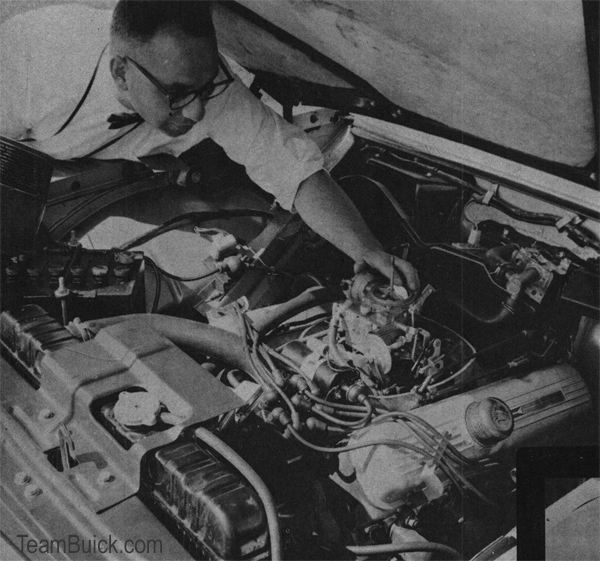

Buick rockers sit almost straight up, just as the larger V8. The easily accessible distributor is at the front.

This section through manifold shows two quarters. Riser from carb is sectioned at top. All Passages are in a water jacket.

Buick's conventional snorkel silencer does not have cast rib at manifold base.

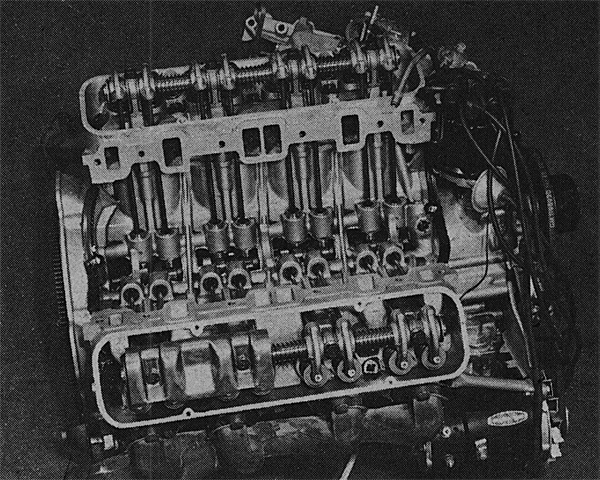

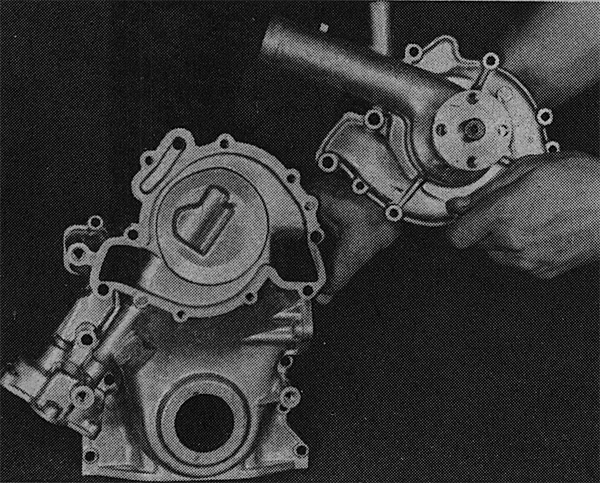

All accessory parts (left) have considerable amounts of aluminum in them. Die cast timing case cover houses parts of various components. Complete Buick engine above weighs 318 pounds, develops 155 bhp @ 4,400 rpm.

Semi-permanent means the use of a combination of permanent molds for the outside of the block and the tappet valley, while sand cores are used for the water jackets and the inner bulkheads. There are high silicon aluminum alloys that would allow direct use of pistons and rings against the aluminum. On the other hand, these alloys are expensive, and more difficult to machine than the alloy selected for the 215 inch block.

To ensure good cylinder life, centrifugally cast iron sleeves are used. It should be added that this type of sleeve allows closer selection and control of desirable wear characteristics than even a normal cast iron block,as the sleeves are relieved of the need for carrying great structural loads. An eight pitch thread cut .005 to .015 inches into the outsides of the cylinder liners retains them in the block after the aluminum is poured.

Even though aluminum expands more than cast iron, the sleeves never become loose because they are closer to the heat source and because there is an unavoidable heat barrier at the junction of the sleeves with the block. The crank is a conventional cast alloy iron unit, fully counter-balanced, with large journals and a 3/4-inch overlap between mains and rod journals. The main bearing diameter is set at 2.2986 inches and width is .802 inches except at the number three main which takes up end thrust and is .821 inches wide.

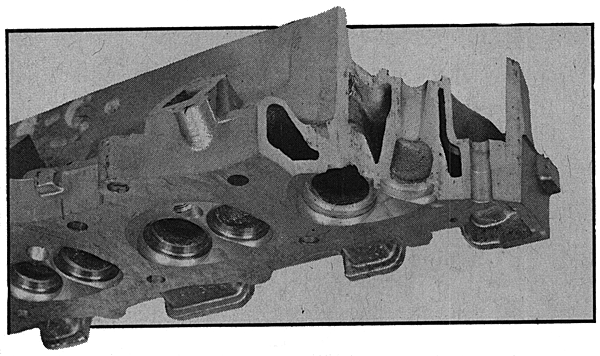

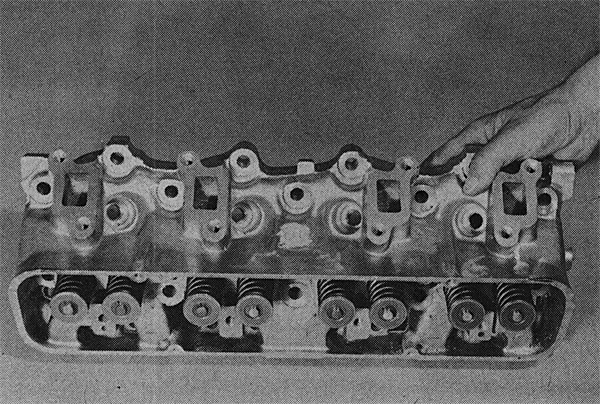

Fully-machined combustion chambers and typically Buick design characterize excellent aluminum heads seen here.

Accessibility and ease of service are highlights of Buick engine compartment.

Spark plug boss is water-cooled as are valve guides. Special press fit holds guides in place. Removal of manifold reveals embossed sheet metal valve cover doubling as manifold gasket. Pad at top of cover prevents drumming, aids silencing.

A hefty rubber-mounted vibration damper testifies to the care used in making the first aluminum engine a smooth running one. Deep skirts on the sides of the block extend beyond the bottom of the main bearing caps, contributing to rigidity and good crankshaft support. The main bearing caps are made of cast iron.

The short stroke presently used (2.80), can probably be extended to three or 3.25 inches to offer a displacement of 230 or 250 cubic inches. Incidentally, this is the only possibility of increasing displacement on this engine, as the dry liners in the block are only .093 inches thick and will not allow boring beyond .030 oversize, a meager gain at best.

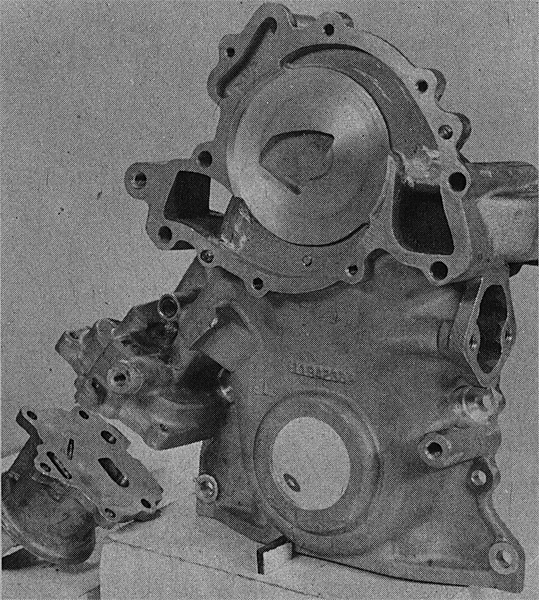

The die cast timing case cover accurately locates the rope-type oil seal at the front of the crankshaft. A protrusion around the seal and an effective slinger keep most of the oil away from the seal, reducing the amount of fluid they must control. In addition, a ridge cast into the inside of the timing case cover acts as a roof over the seal, and further contributes to keeping most of the oil away from it. The timing case cover also serves as the fuel pump mounting and as the housing for the oil pump. While Oldsmobile uses an optional oil filter, Buick carries the oil filter as standard equipment. When the filter is used, it replaces a large size plug at the bottom of the housing.

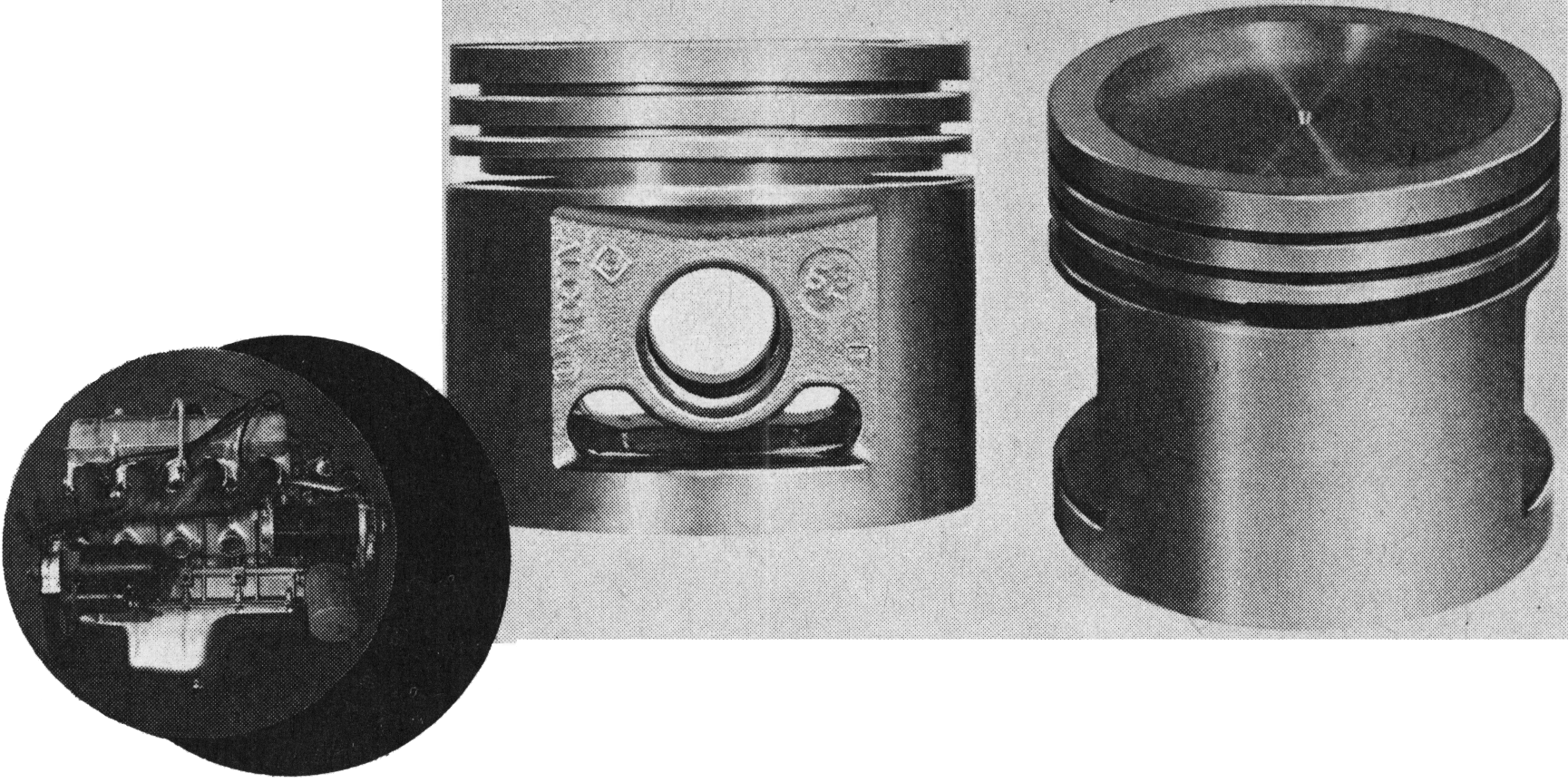

The forged rods are quite short (5.660 inches center-to-center) and light (17 1/2 ounces). Wrist pins are pressed into the rod and float in the piston. This eliminates the need for wrist pin retainers in the piston or rod bushing. As in good aircraft practice, the wrist pin is very thick to avoid wall deflections under load.

The pistons are all aluminum, without expansion control inserts. The conventional slots are placed between the skirt and the head of the piston at the bottom ring groove, forming a heat dam and leaving the head tied to the skirt only in the areas above the wrist pin bosses. When the top of the piston warms up, it expands equally in all radial directions.

At the points where it is tied to the skirt, a hoop effect takes place with the skirt being pushed outward at the wrist pin bosses and, therefore, pulling in at the thrust faces

The cam-ground piston is narrower across the wrist pin bores than at the thrust faces. When the piston expands in the bore, the thrust faces are pulled inward. Slap at the thrust faces is controlled whether the piston is hot or cold. In customary strut designs, a steel strut is put to work accelerating, or amplifying, the hoop motion. In Buick and Oldsmobile's all-aluminum piston, the stiffness of the webs which tie the piston crown to the wrist pin bosses is balanced against the stiffness of the skirt, itself, to achieve the needed hoop action.

The bottom of the piston skirt forms a full hoop. Buick feels that this sis stronger than slipper piston designs of equivalent weight and helps control the action of the piston in the cylinder. Two large size slots separate the bottom of the piston skirt from wrist pin bosses. This avoids skirt distortion and any restraining action which the skirt may have on the pin bosses. If you consider a wrist pin as a beam which is supported in the middle and loaded at the ends, some deflection becomes inevitable. The best solution for retaining maximum bearing area at the pins is to let the bosses flex with the pin.

Buick and Olds differ drastically in combustion chamber design. Olds has a wedge-type chamber, flat top pistons and a port configuration which largely resembles that of the larger Olds engine. Buick has a machined chamber of comparatively small volume and dished pistons. The valves on the Olds are angled to line up with the slant roof of the combustion chamber. On the Buick, they are placed almost straight up, and the port design is of course closely akin to that of the larger Buick engine. Even valve cover placements are distinctively those of their larger engine counterparts.

Buick claims a more favorable surface to volume ratio at combustion time, together with a central plug location and very short flame travel through the major portion of compressed air fuel mass. The squish area is distributed all around the piston and combustion chamber, creating a favorable turbulence. These dished pistons are quite reminiscent of those which enabled GM Research to run some very interesting tests at compression ratios ranging from 10:1 all the way to 25:1, or six points higher than with most diesels.

The use of a dished section makes compression changes quite simple, and we might add that the use of a flat Olds piston in a Buick 215 would result in a compression ratio of 11:1. Where a dish is very deep and falls below the ring belt, some distortion can occur at operating temperatures and added heat is transferred to the piston. However, here the dish is so shallow as to have no practical effect.

Engine cooling is quite elaborate. The aluminum water pump is bolted to the die cast timing case cover which also serves as the back of the impeller housing. Each of the two headers cast within the timing case cover leads directly to the corresponding cylinder bank. The coolant flows though the banks and up to the rear of the heads. After reaching the front of the heads, the coolant is then directed though the manifold to the radiator.

To insure quick and even warm up, the coolant must first course from front to rear along the underside of the manifold risers before returning to the radiator.The use of water as the source of manifold heat eliminates corrosion and a heat riser valve that traditionally rattles and sticks.

Block water jackets extend the full length of ring travel, plus a good 1/4 inch. The spark plug bosses are completely surrounded by coolant. Decks at the head and block are almost entirely closed, except for an opening at the rear of the block. As the heads are interchangeable from side to side, symmetrical openings are used front and rear. Thus, all of the coolant is directed through the block and head.

The slanted portion of each cylinder bank being partially above the openings at the rear, some venting is needed to avoid trapping air pockets during filling. Here again, we come to a difference between Buick and Olds. Olds uses four quarter-inch "steam holes" to vent the upper part of the block. "Steam hole" is actually a misnomer, for they are only vents. Buick, on the other hand found the four holes unnecessary and uses only one small one at the front of each bank.

As you notice, the cooling systems use aluminum almost exclusively, except for the embossed steel gaskets. Hence the possibility of galvanic corrosion is considerably reduced. We asked specifically about special anti-freeze and were told by Buick that there were no plans or call for any at the present. The use of aluminum, with its high thermal conductivity, in the large cylinder block and head areas has enabled radiator size to be scaled down an appreciable amount in comparison to the area needed for equivalent cast iron engines of the same power.

The blocks are fully lead tested when partially machined, and again when completed. If the leakage exceeds specified rates, they are impregnated. Over that, they are scrapped. Impregnation of both pressure and no-pressure types is used. Dry sealant pellets are added as a purely precautionary measure.

The cylinder heads use copper-in-filtrated, sintered iron inserts on both intake and exhaust valve seats. Valve guides are cast iron, pressed into the heads. Although no drastic improvement has resulted from the use of aluminum as cylinder head material, there is a slight gain in mechanical octanes and a reduction of, or even elimination of, potential hot spots. A rocker arm shaft rather than GM's favored ball socket arrangement is used. Part of the reason is that the push rods are offset. Also, it would be difficult to retain rocker studs in the head by press-fitting them, and threads would be too expensive both in production and assembly,. Full gallery oil pressure is supplied to the rocker shaft through passages in the block head and a rocker shaft bolt. The openings for oil supply to the individual rockers are moved out of the load area to increase flow.

The camshaft is cast iron, and has fairly mild timing. A sintered iron cam keyed on the camshaft operates the fuel pump, Hydraulic lifters are used as standard equipment, and the differences in expansion between steel and aluminum may well make them essential for noise reasons. The tappet valley is covered by an embossed steel section that also serves as the intake manifold gasket. By relieving the manifold of duty as a valley cover, much webbing between the risers can be eliminated with resultant weight saving. A foil-covered insulation bag laced between the manifold and the embossed cover eliminates noise and drumming.

Oldsmobile manifold have cast-in-bases for air filters, which increase the silencer volumes and are claimed to reduce noise. Buick uses a snorkel type air cleaner and eliminates some of the manifold complexity. Our trained ear couldn't detect any appreciable difference between the two.

The advert of the aluminum engine will not only herald a new era in engine weight reduction., but also the building of many specials which, until now, had to be on the ponderous side. A saving in engine weight cannot be estimated on the basis of weight difference with an equivalent cast iron unit. There are also attendant weight savings in frame structure, drive train size, etc. These new Buick and Olds engines will undoubtedly influence the future of the automotive industry.